George Ohr (1856–1917), crumpled vessel, Biloxi, Mississippi, ca. 1895–96. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 2 1/2". (Courtesy, Rago Auctions, ragoarts.com.)

George Ohr, cardholder, sculpted hat, and Bank, Biloxi, Mississippi, ca. 1885– 1900. Lead-glazed earthenware. Cardholder, 4 1/4 x 4 1/4 x 3 3/4"; sculpted hat, 2 1/4 x 3 x 4 1/4"; bank, 4 1/4 x 5 x 5". (Unless otherwise noted, all photos courtesy of the author.)

Portrait of George Ohr. From George Ohr, “Some Facts in the History of a Unique Personality,” Crockery and Glass Journal 54 (1901).

Postcard, The Biloxi Pottery, Biloxi, Mississipi, Detroit Photographing Company, 1901. (Collection of the author.) This postcard features a photograph of Ohr’s second studio, which was built ca. 1895.

George Ohr, token, Biloxi, Mississippi, ca. 1885–1900. Unglazed earthenware. D. 1 1/4". (Collection of the author.)

George Ohr, token, Biloxi, Mississippi, ca. 1885–1900. Unglazed earthenware. D. 1 1/4". (Collection of the author.)

George Ohr, token, Biloxi, Mississippi, ca. 1885–1900. Unglazed earthenware. D. 1 1/4". (Collection of the author.)

George Ohr, token, Biloxi, Mississippi, ca. 1885–1900. Unglazed earthenware. D. 1 1/4". (Collection of the author.)

George Ohr, token, Biloxi, Mississippi, ca. 1885–1900. Unglazed earthenware. D. 1 1/4". (Collection of the author.)

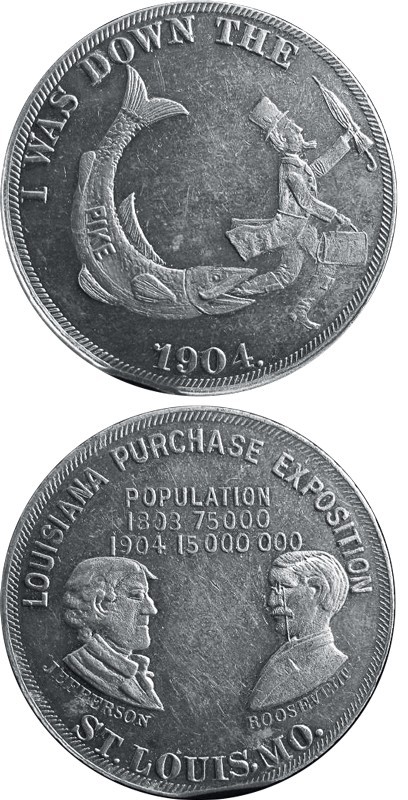

Louisiana Purchase Exposition commemorative medal, St. Louis, Missouri, 1904. Aluminum. 1 1/2". (Photo, courtesy of Jeff Shevlin, So-CalledDollar .com.)

Louisiana Purchase Exposition commemorative medal,St. Louis, Missouri, 1904. Aluminum. D. 1 3/8". (Photo, courtesy of Jeff Shevlin, So-CalledDollar.com.)

WITHIN THE POTTER George Ohr’s oeuvre of nearly ten thousand ceramic objects, consisting mostly of vibrantly colored and extremely manipulated hand-thrown pots (fig. 1), are six clay tokens. Though trinkets and baubles such as banks, cardholders, and paperweights (fig. 2) are also mixed in, the tokens are in a category of their own. They bear no glaze, no severe manipulations, and no maker’s mark. They are made from molds, whereas the rest of the collection is hand-thrown or a built one-of-a-kind creation. Ohr, who prided himself on the exceptional singularity of most of his objects, makes no mention of the molds in extant documents (fig. 3). Perhaps most striking are the obscene sexual messages they bear, formed using combinations of letters, numbers, and images.

The tokens have largely been overlooked by critics in favor of the more conspicuous vessels forms. It it is not known when they were made, if/where they were sold, what they cost, how popular they were, or who bought them. Perhaps they have also been overlooked because they are so anomalous to the remainder of the oeuvre. Taken by themselves they are easily written off as commonplace trinkets, but their brazen messages are anything but commonplace and, unlike the unremarkable bank card or cardholder, they express a sentiment not applicable to most moments or places in one’s daily life. They could not be kept on one’s desk nor handed out at the corner store. One might be reluctant even to carry one in one’s pocket on most occasions. However, put within their proper context these tokens emerge as souvenirs of prominent sites of fantasy in the last quarter of America’s nineteenth century.

This article will offer suggestions as to the tokens’ proper function within their intended context. In order to better understand them, it is necessary to know something about their creator and the time in which he existed.

George Ohr (1856–1917) and the Gilded Age

In the 1960s, antiques dealer James Carpenter discovered thousands of dust-covered pots stacked in the attic of the garage of George Ohr’s sons in Biloxi, Mississippi. The pots, created by George Ohr, Biloxi’s famed “Mad Potter,” had been stored there for over a half century, ever since the potter’s retirement and subsequent death. Carpenter’s discovery thrust Ohr’s odd clay creations onto the stage of the 1960s’ art world.[1]

Ohr’s contorted, abused forms, which he often coated in vibrant, blistered glazes, have become highly prized, routinely fetching multiple thousands of dollars at auction, and have been collected by such famed artists as Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns. Art critics and collectors of the 1960s and later were taken by Ohr’s strange, unconventional style. Most American art pottery of the nineteenth century was pure and serene in design, often borrowing its shape from Chinese or Greek vases. Ohr’s collapsing shapes and bleeding glazes appeared to both emulate and mock the popular styles of the day, and came to be seen as ahead of their time, akin to the totemic symbolism of the abstract expressionists.[2]

Before all his posthumous fame, however, George Ohr was a spirited, eccentric potter and self-promoter living and working in the period that has come to be known as the Gilded Age, a tumultuous and formative time in the nation’s history.

As gilding is a thin covering masking a baser material, so too did the increased wealth and material well-being of the Gilded Age mask underlying socioeconomic and spiritual turmoil. It saw the emergence of largescale corporations and mass production, as well as the advent of modern mass culture—new forms of advertising and commercial display as well as a proliferation of newspapers, magazines, and books. Conversely, various threads of individualism combated the increased mechanization of society, and socialism fought the unequal distribution of wealth. Darwinism undermined traditional religious beliefs while a more general spiritualism developed. The country was torn between progress and tradition, wealth and despairing poverty, American ambition and citizens’ rights.

As a Southern craftsman, independent businessman, shrewd self-promoter, and sympathizer to socialist causes, Ohr was enmeshed in the zeitgeist of his time. Little primary documentation exists about him, but we do know that he learned to throw pots from a family friend living in New Orleans, and that as soon as he knew how to “boss a little piece of clay into a gallon jug” he took off on a two-year, sixteen-state sojourn to learn all he could about the process and business of pottery, and “never missed a show window, illustration or literary dab on ceramics since that time, 1881.”[3]

When he returned home, around 1883, Ohr started his own studio and set out to become the “World’s Greatest Art Potter.” Like all good businessmen, he recognized the importance of having a gimmick, and his long handlebar mustache and eccentric writing style became his trademarks. This observer’s description is typical of the impression Ohr made:

Entering the house that Ohr built, you find, bending over his wheel or patting into shape—more probably out of it—his latest creation, the potter himself. His eyes hold you first—wonderful eyes, big, bright, brown, wild like those of a startled animal. And then your gaze gets tangled in the meshes of his mustache and so lost for awhile. For it is impossible to tear your fascinated eyes away until they have followed all the twists and turn of that hirsute ornament and discovered its ends as they curl for the third time about his ears.[4]

Samples of Ohr’s writing, which can be found in contemporary journals and newspapers across the country as well as etched into his own pottery, are just as telling of his eccentricity:

Now then, my Dear, Good Readers, and all the rest of yease . . . let me radiate & while U R reading, don’t think between D lines, ‘Smart Aleck, damphool potter,’ etc. A duck doesn’t knead his brains 2 float as he is built 2 hold water, B in it & stay dry & I don’t need any 2 mash mud or push a pencil, Because I’m built that way. . . .[5]

Ohr’s writings are often confusing and take some time to comprehend. Here, he deliberately confuses the appearance of the passage: he used “damphool” for “damn fool” and “knead” for “need,” even though neither misspelling actually changes the pronunciation of the word. In fact, he spelled “need” correctly later in the same sentence. Further, the only function his consistent use of numbers and letters for words—as in 2 B for “to be,” U R for “you are,” and “D” for “the”—served was to confuse and dramatize the paragraph visually, not to aid in pronunciation. Ohr’s inimitable phrases, such as “mash mud” (make pottery) or “push a pencil” (write) were not reflective of his regional dialect, only of his distinctive way of writing or talking. Clearly he was trying to make an impression on the public by consciously emphasizing his peculiarities. It is important to note that there is a tradition among Southern characters to phonetically manipulate their words in order to emphasize the “dumb” Southern persona that readers and audiences of the North had come to expect. A good example is Sut Lovingood, a caricature of a stereotypical farmer of rural Southern Appalachia created by the American humorist George Washington Harris (1814–1869).[6]

Given that Ohr was able to support himself and his family as a potter he was a success, but his life and career were marked with ups and downs. He and his wife suffered the loss of five of their ten children. In 1893 his first studio burned to the ground, along with many pots. Nevertheless, he achieved recognition from critics across the country, was included in Edwin Atlee Barber’s Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, and was even the inspiration for the main character of a novel.[7]

Despite those accolades, Ohr never felt he got the recognition he deserved. To him, each pot was a one-of-a-kind masterpiece worthy of museum collections and critical acclaim. Twice he sent unsolicited samples of his wares to museums and both times museum officials chose a few pieces and returned the rest. Ohr had not intended for the samples to be broken up, saying “To distribute what I have is like distributing a poets work—by giving hundreds of lines too [sic] hundreds of creatures—hundreds of miles apart.” This continued rejection, perceived or real, wore on Ohr and in 1908 he quit making pottery, boxed his wares up, and tucked them away in the attic of his sons’ car garage, to be discovered almost fifty years after his death by James Carpenter.[8]

As is often the case, one’s impact is often recognized in retrospect. After Carpenter found Ohr’s pots, Ohr was celebrated for his cutting-edge ceramic forms despite his relative isolation in Biloxi, Mississippi, and he was characterized as “the most prescient prophet in Western ceramic art.”[9]

Ohr was not isolated, unaware, or unaffected by his time period, however. He knew enough about the shifting consumer culture to create a distinct and noticeable persona for himself, one that played to his specific consumer base and Northern expectations of Southern craftsmen. He built an eccentric pagoda-shaped studio (fig. 4), which towered over the other buildings in Biloxi and advertised his own over-the-top products. He was a socialist in a time when capitalism ruled the American economy.[10] And then, of course, there is his pottery. Just as eccentric and deliberate as the rest of the man, his pots were disfigured, functional forms rendered unusable, and coated in grotesque colors and textures.

Given his response to the world around him, it is difficult to think of his tokens as mere trinkets or gags, unrelated to events surrounding him.

Ohr’s Tokens

The entirety of Ohr’s token collection consists of six double-sided clay coins bearing pictures, words, and numbers combined to form twelve messages, all crudely sexual. Five of the six known designs are illustrated in figures 5–9. The design and message of the tokens differ very little; some have ridged perimeters and some are smooth, indicating at least two different casts. The least offensive message reads:

Good for one screw

I love you dear

Give me some

A Screwing Match

Let’s go to bed

Because of the nature of the pictographs on them, these coins are sometimes referred to as “brothel tokens,” although there is no evidence they were ever used as such. They certainly carried no currency in actual brothel houses nor did they name specific businesses or locations. Ohr did not sign or date them, nor did he write about them as he did his other pots. Critics have considered Ohr’s tokens to be trinkets or “novelties,” not of the same significance as his other pots. The terms novelties, trinkets, and gags suggest that Ohr’s tokens were playful—even clever—but ultimately meaningless. They are still collected even though they do not fetch anywhere near what his art pots would. To this day their purpose remains unknown, but two important events of this time period seem likely sources of inspiration: the phenomena of world’s fairs, and Storyville in New Orleans.[11]

Ohr at World’s Fairs

Ohr attended numerous world’s fairs, including the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans (1884–1885), the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893), the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta (1895), the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo (1901), and the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in Saint Louis (1904).

World’s fairs were a chance for countries and regions across the world to showcase their latest technological, scientific, and cultural advancements. Fairs hosted by American cities were typically organized to celebrate American bravery or achievement. For example, the New Orleans’ World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition celebrated the 100th anniversary of the cotton industry; the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893) was organized around the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s “discovery” of the New World; and the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (1904) commemorated perhaps the greatest land bargain in U.S. history.

While research has shown that world’s fairs held in the United States during this period overwhelmingly emphasized the accomplishments of white people, they nevertheless celebrated human achievement and drew enormous crowds from across the country, resulting in significant cultural influence across all classes of society.[12]

Crowds flocked to buildings designated for fine arts, mines and metallurgy, machinery, agriculture, forestry, and the like, but another big draw was the “midway section,” a standard feature of every major show. Although the name of the area might have been termed something different from fair to fair, the content was the same: a carnivalesque atmosphere that trafficked in spectacle and vendors not suitable for the mainstream program, which purported to be more educational. Not surprisingly, it was in the midway section, not fine arts, that Ohr could be found.

In its pamphlet, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in Saint Louis (1904) termed its midway section “the Pike”:

What was the Pike? The Pike was whatever the fantasy of the beholder wished to make it. It was the carnival and sideshow aspect of the fair. So famous were its attractions, that for all time in the future, listless withouta-care personas would be called Pikers. It was an adventure for those who seldom dared the risque, and a fertile area for those who dealt in such vices which skirted the acceptability of the law. It was a child’s fantasy of allure and adventure.[13]

The Pike contained such exhibitions as the U.S. Navy, the Galveston Flood, the South Sea Islands, the Curious Cliff Dwellers, the Esquimaux, a Chinese and Japanese Village, streets of Paris and Cairo, and more. Although those places actually existed and therefore were not places of fantasy, their geographic, social, and ideological differences were distant enough from the norms of American life that they were described and promoted as such.

Various medals existed to promote the fair and the Pike. Of particular interest to this discussion is one that features a well-dressed man holding a closed umbrella being eaten by a large fish labeled “PIKE” (fig. 10). Along the top left edge are the words “I WAS DOWN THE” and below it the fish biting the man’s leg, with the date “1904” on the bottom. The image of a well-to-do man being consumed by the lowbrow curiosities offered by the Pike section of the exposition is a captivating subtext.

Another coin features the Ferris wheel (fig. 11). While not in the Pike area, the Ferris wheel was a notable component of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. The exposition’s wheel had been invented by George Washington Ferris and was built for the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893). Despite its success in Chicago, Ferris declared bankruptcy after the fair closed and died of typhoid fever a couple years later. A wrecking company bought the wheel and sold it to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. Clearly, the Ferris wheel was a destination in and of itself by the time it reached Louisiana.[14] The Louisiana Purchase coin featuring the Ferris wheel pictures the wheel surrounded by the words “You Have Got to Show Me, I’m From Missouri” and “World’s Fair St. Louis 1904.” The reverse of the coin is especially interesting. It reads “Presented for Having the Largest” accompanied by an image of a rooster, or cock.

The double meaning of the cock is surprisingly close to Ohr’s own use of the word, especially given that this particular pictograph had not yet proven to be very common. While it is premature to say that Ohr was influenced by the Louisiana Exposition or any other exposition, it is fair to assume that he would have encountered souvenir tokens like these. This coin is visual confirmation of two important suppositions regarding meaning and purpose behind Ohr’s clay tokens: that obscene image and wordplay were part of the culture of world’s fairs; and that monetary value need not be attached to such coins. They could have acted as souvenirs or promotional items handed out free of charge.

The midway area of world’s fairs was promoted as a realm of fantasy. An opportunity to safely walk on the wild side and experience the thrills and spectacle far beyond one’s own backyard. It was no matter that these sites of fantasy were based on geographically real places. The spectacle surrounding them heightened the drama and encouraged the fantasy. This particular world’s-fair space was a controlled free fall.

Ohr and Storyville

Another popular site of fantasy, Storyville, also emerged during this time. Storyville was not the first but probably the nation’s best-known experiment with legalized prostitution. Begun on January 1, 1898, Storyville lasted for almost nineteen years, until the United States entered World War I. At that time the federal government passed a law prohibiting prostitution within a five-mile radius of any military installation, thus forcing Storyville to close.[15] Storyville was a socioeconomic experiment that will be forever remembered in both regional and national history. New Orleans, always a thriving and busy port city, was home to prostitutes and brothels at least since its acquisition by the U.S. in 1803, and undoubtedly before. While prostitution was not actively discouraged, numerous ordinances were passed to control and limit the areas of New Orleans in which prostitutes could ply their trade. Storyville came to be when Alderman Sidney Story introduced legislation denying housing for immoral purposes outside a designated area. Said area, just north of the French Quarter, soon came to be known as Storyville, to Mr. Story’s disgust. By confining the highly lucrative profession of prostitution to a single area, officials hoped to manage the illicit practice while taxing the businesses and systematically and legally reaping its benefits for the greater good.[16]

Ohr frequented New Orleans in the years prior to Storyville’s beginnings: during the first half of the 1880s he was a student of Joseph Meyer’s in New Orleans; from 1885 to 1890 he worked at the New Orleans Art Pottery; and in 1889 he lived at 249 Baronne Street, just three blocks south of Basin Street, a main thoroughfare in Storyville. Though these dates are several years prior to Storyville’s beginnings, it isn’t hard to accept that Ohr would have continued to travel there, especially given the business opportunity that Storyville presented.[17]

Ohr’s coins were not used as currency, but other tokens did function that way in Storyville’s houses. According to Louis Crawford and Glyn Farber, authors of Louisiana Trade Tokens, the only book to index and research the various trade coins used in Louisiana, “[t]okens were . . . used in houses of ill repute, primarily in the famed ‘Storyville’ district of New Orleans. . . . The customer would buy the token from a contact (often the bartender) and after services were rendered, he would give the girl the token plus whatever tip he deemed sufficient. In this way, the Madam was assured of getting her cut while the girl was able to keep all her tips.”[18]

The authors further note that “[s]everal tokens are known from businesses that have been documented to be connected with brothels, but since most indicate a numerical redemptive value they may have been simply bar checks rather than ‘house’ tokens.”[19] A coin for the Arlington Saloon reading “Good for 5¢ in Trade” is a good example. Exactly which “trade” the coin holds value for is undefined.

Ohr’s coins do not resemble the tokens used in Storyville, which were largely about identifying worth and trade-for-service value. Indeed, none of his coins denotes any financial value with one exception, which reads “Good for one Screw.” Ohr’s tokens are so different in design and meaning because he was not attempting to sell a service. Instead, he was offering a souvenir, a memory and reminder of the wild times and fantasy of Storyville.

Brothel tokens, whether exchanged for value or not, are not real currency. Abstractions of value from an already abstracted system of value, they have worth only in a very specific place for a very specific thing. They cannot be carried down the street and used to purchase a candy bar. Likewise, the face value of a coin is not accurate—that is, the amount of money needed to purchase a single “screw” is far more than the value of a coin reading “Good for One Screw.” While some brothel coins could be redeemed for actual service, particularly in Storyville, they largely dealt in the realm of fantasy.[20] Ohr’s tokens drop the currency pretense completely, and exploit the crude and authentic fantasy around which Storyville was built. In this light the vulgarity of his coins not only make sense, but are well suited to the atmosphere:

Leave me feel your cock

Give me some

Let’s go to bed

Put it inside

Can I screw you

Ohr’s Tokens and Gilded Age Fantasy

The Gilded Age was a tumultuous time, as described above, but also a time of increased fantasy. Amusement parks, dime museums, burlesque shows, and vaudeville shows, enabled by increased disposable income and free time, flourished. Such sites of fantasy were also a response to the tectonic shifts in social roles and identity that the modernizing force of mechanization instituted. Mechanization shifted the social meaning of strength and fitness from the physical to the financial. For many, a workday in the Gilded Age often meant sitting in an office or managing workers, not working one’s own land or performing physical labor. Long-established traditional roles of men and women within society were changing, too. If the traditionally male-dominated workforce no longer required physical strength, then how was masculinity measured? And why could women not hold those positions? Newly arising amusements were designed to emphasize fantasy that would help audiences escape the realities and stress of a culture in flux.

Within this context our understanding of Ohr’s tokens gains mass. While perhaps still mere trinkets or souvenirs, like all souvenirs they are physical manifestations of memory, made significant because of personal experience. His coins were designed to recall lowered inhibitions and libidinous freedom. A memento of a controlled free fall, like the experiences viewers and participants would have had at Storyville and the midways of various world’s fairs. In this way Ohr’s tokens are also cultural artifacts of the Gilded Age, a time of shifting American ideals and ways of life.

The moniker “Mad Potter” has been used by various authors to describe Ohr, most notably in The Mad Potter of Biloxi: The Art and Life of George E. Ohr by Garth Clark, Eugene Hecht, and Robert Ellison (New York: Abbeville Press, 1989).

Garth Clark, “George E. Ohr: Avant-Garde Volumes,” Studio Potter 12 (1983): 10–19.

Only about twenty-three articles about Ohr exist that were written during his lifetime. They include autobiographical sources, such as his own three-page autobiography “Some Facts in the History of a Unique Personality,” Crockery and Glass Journal 54 (1901), from which the quote is drawn.

William King, “The Pallisy of Biloxi,” Illustrated Buffalo Express, March 12, 1899, quoting an unidentified observer.

George Ohr, “Letter & Answer No. 2”, 1903. From loose pages of an unidentified journal found at the Biloxi Public Library.

See Carol Boykin, “Sut’s Speech: The Dialect of a ‘Nat’ral Borned’ Mountaineer,” in The Lovingood Papers, edited by Ben Harris McClary (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1965).

Buffalo art critic William King wrote about Ohr in “The Palissy of Biloxi,” Illustrated Buffalo Express, March 12, 1899, 4. Edwin Atlee Barber was a noted authority on pottery and author of the seminal Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, 2nd ed. rev. and enl. (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1902). The character fashioned after Ohr is Giacomo Barse in Mary Trace Earle’s The Wonderful Wheel (New York: Century Co., 1896).

Ohr sent samples to both the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C., and the Delgado Museum of Art, now the New Orleans Museum of Art. George Ohr, “Biloxi Heard From: Geo. E. Ohr Thinks He Is the ‘Missing Lynx,’” Crockery and Glass Journal 53 (1901), quoting Times-Picayune, October 1894.

Clark, “George E. Ohr,” p. 19.

Ohr was affiliated with the Mississippi Socialist Party of America and contributed to The Appeal to Reason, a prominent socialist newspaper published from 1895 until 1922.

Eugene Hecht and Robert Blasberg repeatedly use the terms novelties, trinkets, and gags when describing and categorizing Ohr’s wares in their books After the Fire: George Ohr, an American Genius (Lambertville, N.J.: Arts and Crafts Quarterly Press, 1994), and George Ohr and His Biloxi Pottery (New York: J. W. Carpenter, 1973), respectively. Garth Clark in The Mad Potter of Biloxi (New York: Abbeville Press, 1989), p. 124, notes that in Ohr’s coins “[t]here were neither ironies nor transformations . . . to make them anything more than novelties.”

See Robert W. Rydell, All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876–1916 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984). Nearly 100 million people visited the expositions held at Atlanta, Buffalo, Chicago, Nashville, New Orleans, Omaha, Philadelphia, Portland, Saint Louis, San Diego, San Francisco, and Seattle.

This account was written by Clifford Mishler, a publisher at Krause Publications, as part of the foreword to the Saint Louis Exposition pamphlet. The pamphlet is published in its entirety in Kurt R. Krueger, Meet Me in St. Louie: The Exonumia of the 1904 World’s Fair ([Iola, Wis.]: Krause Publications, 1979), p. 6.

Information on George Washington Ferris and the fate of his wheel can be found at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/history-ferris-wheel-180955300/.

Pamela D. Arceneaux, Guidebooks to Sin: The Blue Books of Storyville, New Orleans (New Orleans, La.: The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2017), p. 29. It was in Virginia City, Nevada, that prostitutes were assigned to a geographically prescribed area for the first time. Arceneaux also notes that Omaha, Nebraska, and Waco and San Antonio, Texas, implemented similar legislation in the late 1880s.

Various versions of the so-called Lorette ordinance, passed in 1857 and 1865, did not outlaw prostitution but instead tried to restrict it to certain areas. See Arceneaux, Guidebooks to Sin, p. 28. An entertaining outline of Storyville’s beginnings is offered in Al Rose, Storyville, New Orleans (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1974).

The facts of Ohr’s life come largely from his autobiography “Some Facts in the History of a Unique Personality,” Crockery and Glass Journal 54 (1901): 123–25. For information about his association with the New Orleans Art Pottery, see Jessie Poesch, Newcomb Pottery: An Enterprise for Southern Women, 1895–1940 (Exton, Pa.: Schiffer, 1984). Eugene Hecht (After the Fire, p. 14) notes that the New Orleans city directory for 1889 carries the entry: “Ohr George E Potter, r. 249 Baronne,” so we know he was in residence there for at least that year. Hecht confirms that Ohr split his time between Biloxi and New Orleans because his wife, Josie, still in Biloxi, became pregnant with their second son, Leo Ernest, during this time.

Louis Crawford and Glyn Farber, Louisiana Trade Tokens: A Listing and History of the Known Trade Tokens Used in the State of Louisiana, 2nd ed. (Lake Mary, Fla.: Token and Medal Society, 1996), p. 11.

Ibid.

Carly A. Kocurek, “‘Good for One Screw’: A History of Brothel Tokens,” The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/02/good-for-one-screw-a-history-ofbrothel-tokens/283915/.